On a recent trip to Taiwan, I found a time-stained book about bardo, a Tibetan term for being in between states. It described what I was feeling; in between being young and being old, passing from one phase of life into another. I'm drying out. I'm turning into beef jerky, and that's ok? I tell myself to accept the nature of impermanence. I make art to practice forgetting, letting go, and dying. Ironically, my sculptures, installations, photos and prints cannot shake the desire to remember, to hold on, and to live forever.

At my studio, I habitually shuffle stacks of 4” x 6” photos like tarot cards. Images of myself, family, friends, school, home, work, and travels were made with my Canon point and shoot camera and processed as c-prints during my adolescent-to-young adult years between the 90's to early 2000's. Lately, I have added digital c-prints from the mid-2000’s until the present to include imagery from my full adult-to-midlife years. Near and distant memories are deciphered to reflect upon the past, clarify the present, and foresee the future.

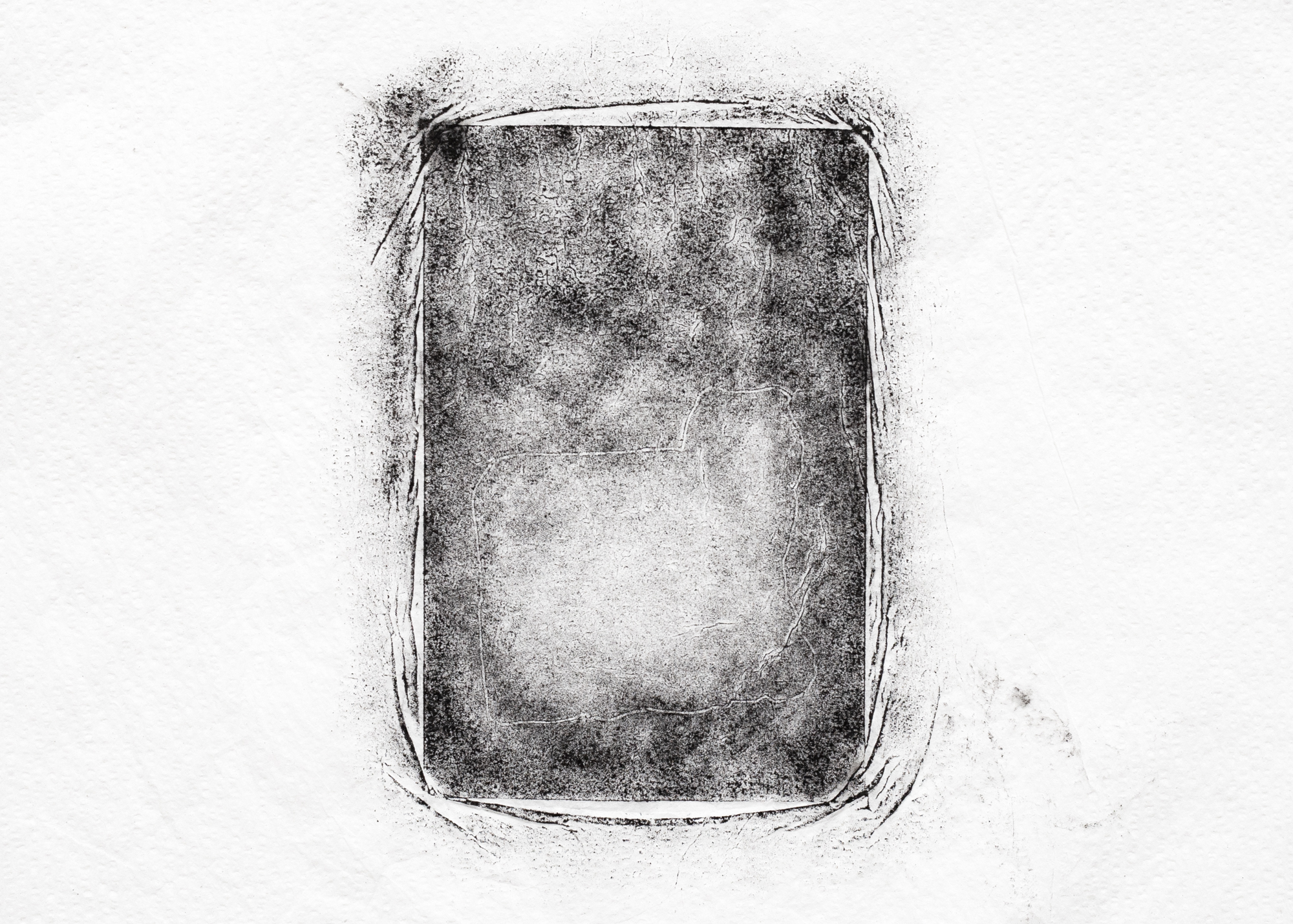

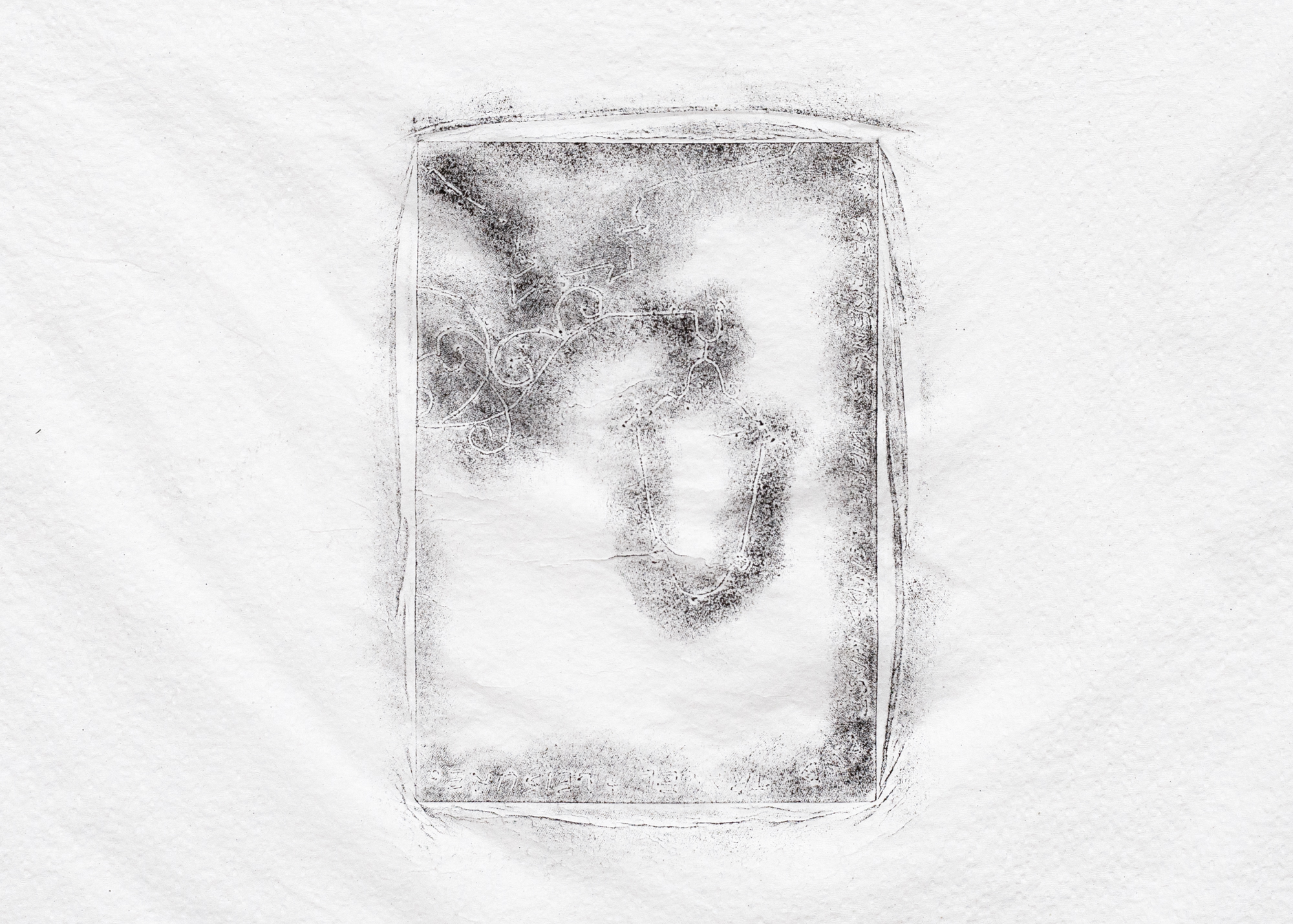

Some of these photos are set aside to be embalmed in clay while others are excised and inked to produce high contrast rubbings on medical drape sheets. Both processes are destructive in their intent to preserve and notably involve the transition from wet to dry states. Clay and paper expand as they are hydrated and contract as they are desiccated. The material characteristics of my work metaphorically parallel emotional and physical expansion and contraction across lifetimes.

At Binghamton University’s Elise B. Rosefsky Gallery, I have made a field of drying racks to receive natural light from two large picture windows. These racks are handmade from unraveled coils of pliable galvanized steel wire straightened into approximated lengths, woven into porous, gridded panels, and folded into standing tents. Thousands of threaded knots bind various points of intersection to stabilize their irregular structures. Precariously, they support the weight of my ink-stained memories on white medical drape sheets. From what I have gathered about beef jerky, thorough sun drying can prolong shelf-life indefinitely.

Bardo, Solo Exhibition, Binghamton University, NY, 8/28 - 9/30, 2025

Public Lecture: 8/28/25, 5:00 - 6:00 PM, Lecture Hall 10 (LH-010)

Opening Reception: 8/28/25, 6:00 - 7:00 PM, Elise B. Rosefsky Gallery (FA 259)

Takming Chuang transforms San Francisco University High School’s Jackson Street Gallery into a holding facility to sort and process 30 years of embodied knowledge. Modular utility shelves hold clay-encapsulated memories shot during the artist’s teens to early 20s. On felt-lined wall boards, original c-prints from the same time period (1995 - 2005) are scattered non-chronologically among digital contemporaries (2006 - 2024). The gallery’s trash, recycle, and compost bins, filled and emptied daily, are integrated within the modular shelves. The title of this exhibition, Cache, alludes to the exponential accumulation of embodied artifacts that individuals hold, sort, and process. Chuang is interested in how individuals keep, discard, and recycle information across time in relation to change.

“Takming Chuang’s works are also sculptural in nature, including photographic elements in unexpected fashion. One piece features a metal drying rack scattered with mango skins, two holding cutout photographic portraits. In another, folded snapshots themselves support the wire frame of a soaking rack, littered with ink rubbings and small, ceramic forms. The sculptural quality of these pieces furthers a distinctly embodied viewing experience that had me, at one point, on hands and knees trying to peer inside Chuang’s folded snapshots.”

-Max Blue, Variable West

San Gallery (Tainan, Taiwan) presents Compressions, a solo exhibition of new work made between 2022 - 2023 by Takming Chuang. Ink rubbings, photographs, sculptures, and floor installations are exhibited within a restored tiled and wood beamed attic.

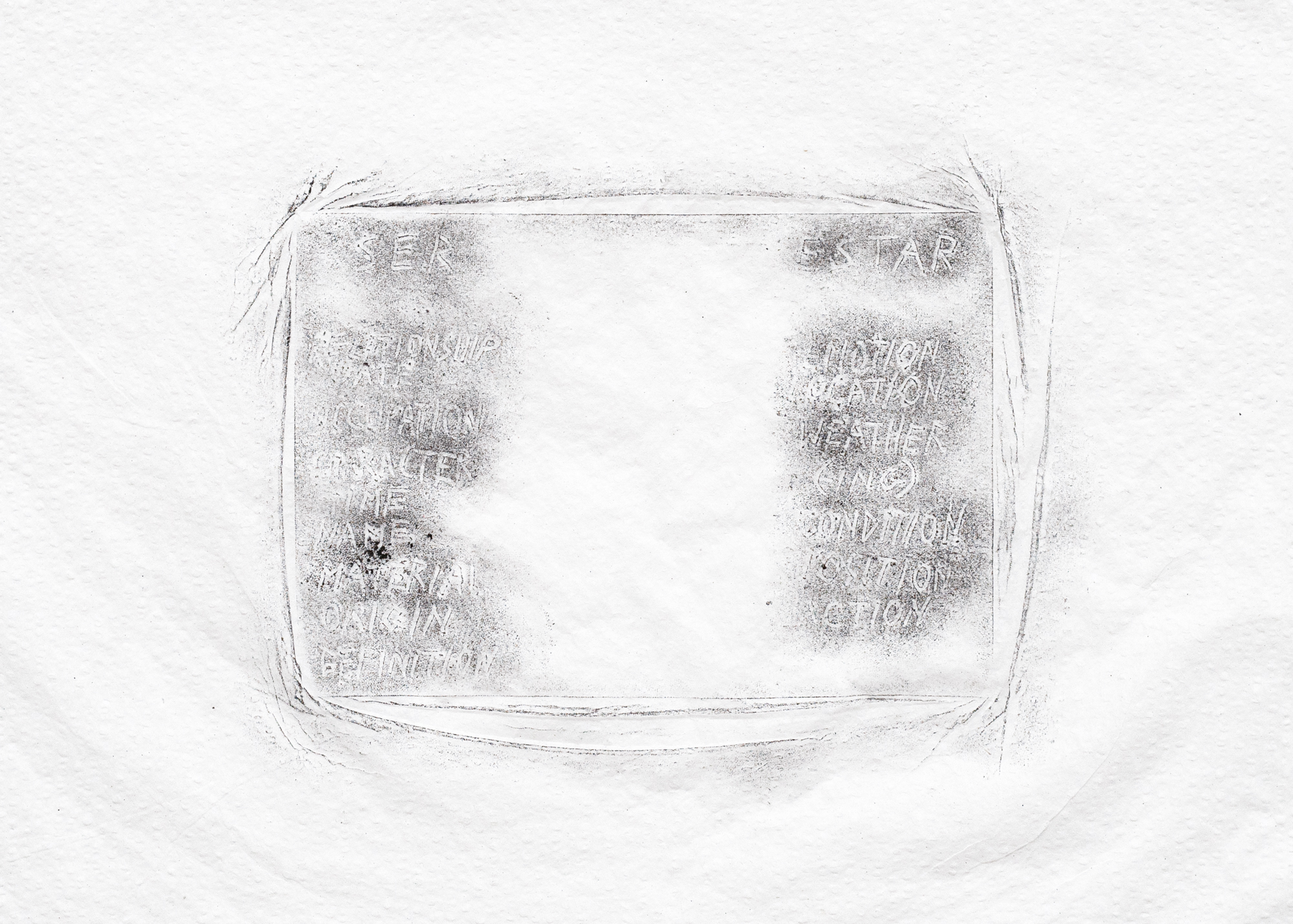

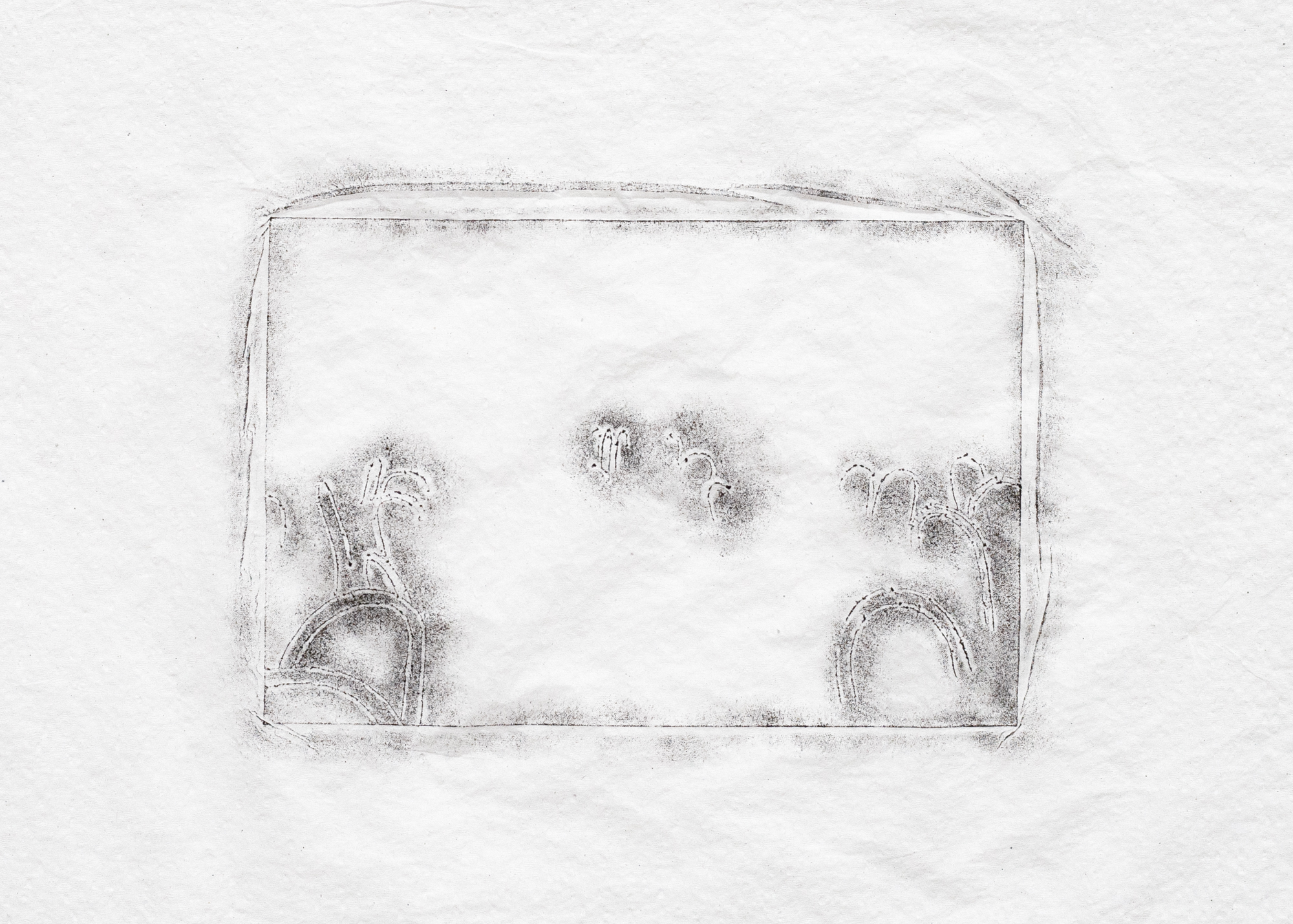

Ink rubbing is a long-established, east Asian art form for the replication, study, and preservation of treasured objects. Historical examples of rubbings include ornamental carvings on jade seals and commemorative Chinese inscriptions on stone tablets. A thin sheet of damp rice paper forms a surface impression. Afterwards, delicate layers of ink are applied with a silk tamp until fine details emerge in high contrast. The result is a faithful and unique record of an artifact’s texture. As an early printing method, rubbings retain the interpretive hand of the maker.

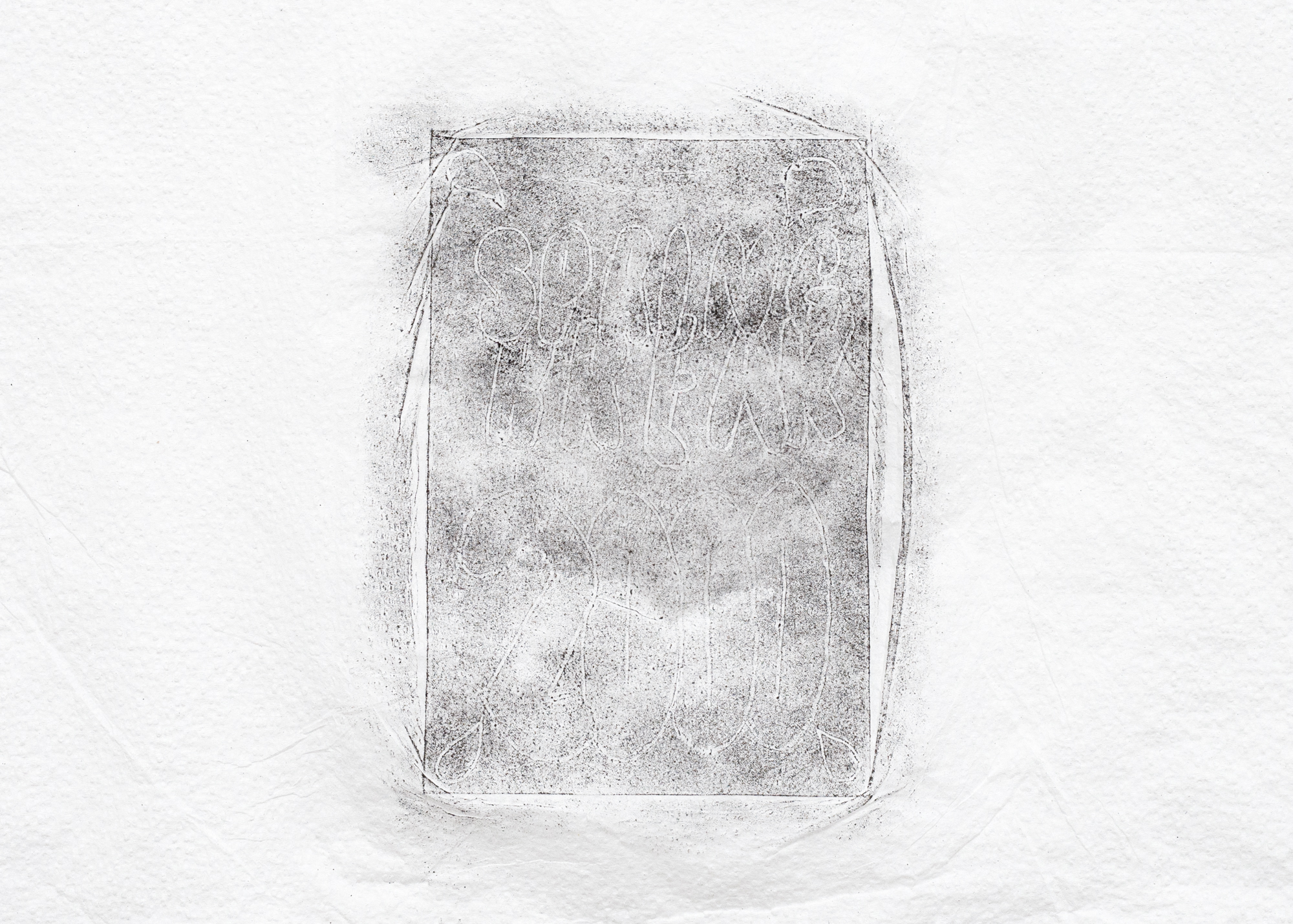

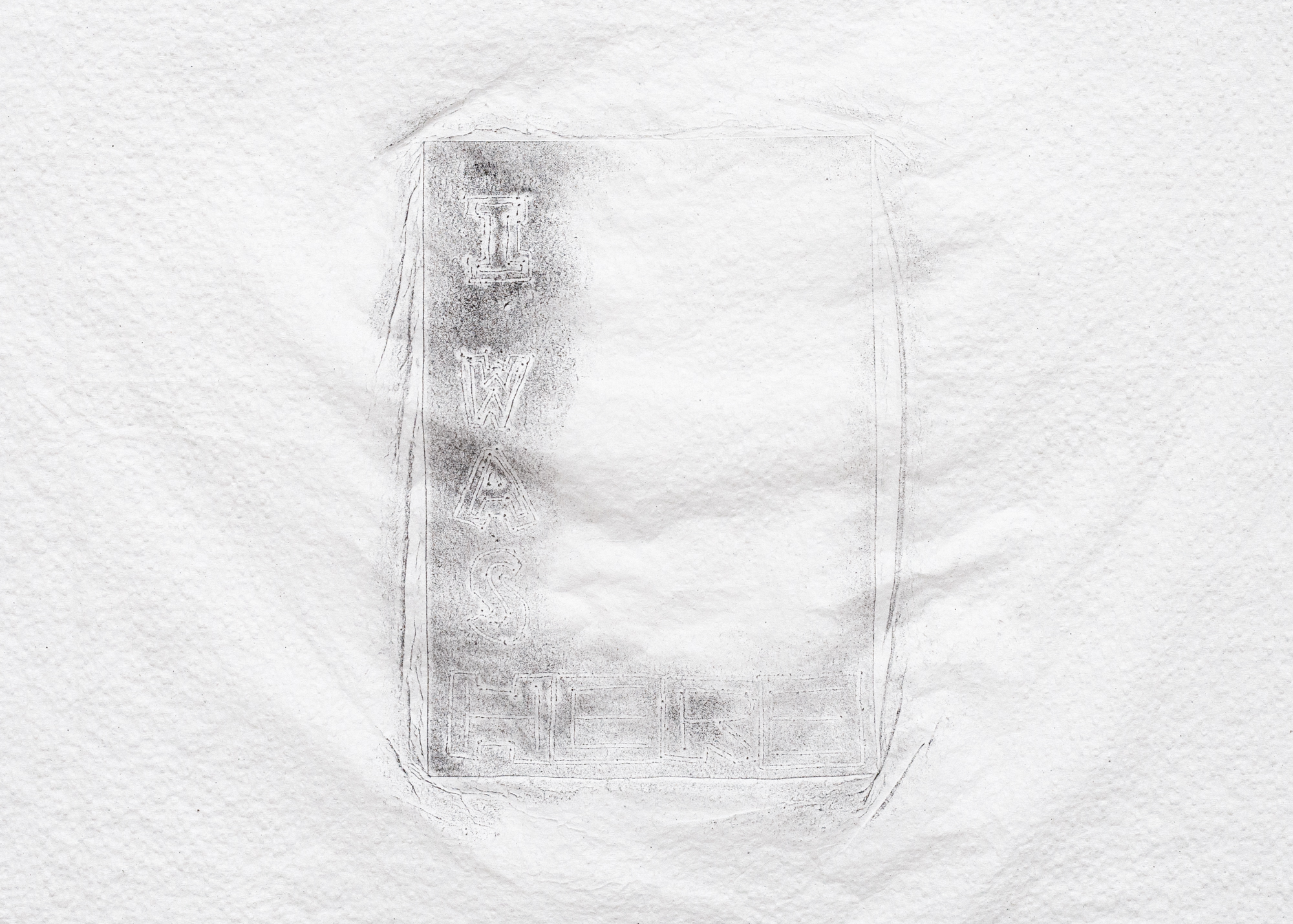

Chuang adapts this tradition to investigate his personal archive of vernacular photographs, taken by the artist in the 1990s - early 2000’s as an adolescent/young adult. He traces or obscures the subjects of his pictures by incising outlines and inscriptions onto the surfaces of original c-prints. These markings are then carefully transferred onto damp clinical drape sheets with Chinese or sumi ink. Unique creases and wrinkles form around the perimeters of each rubbing during the transfer process and can be likened to a fingerprint. Each rubbing is an original, contemporary interpretation of Chuang’s past at home, at school, at work, and during travels. When asked about the photographic medium, “I needed to see my association to people and places through the established format of a 4 x 6-inch picture as evidence of my development. Over 20 years later, these images evidence substantial exterior and interior change.”

In addition to framed work, Chuang’s sculptures and installations combine his original photographs and ink rubbings with hand-bent wire armatures, plastic wrapped clay, and page protectors. A defiant sense of preservation is at play as well as a melancholic acknowledgement of impermanence.

1. Alberti’s Facade

Things look different up-close, in real life. Winter Break as an undergrad, late 90s, my cousin Ellen and I took a trip to Italy and France. One of my highlights was coming across Alberti’s façade for the Basilica Santa Maria Novella in Florence. I learned about the building in an intro to architecture course at Binghamton University. We walked alongside it until the street opened onto a square. I turned around and there it was with a fountain, a bunch of pigeons, and a sunset. Alberti’s façade was a black and white image until I saw it in person.

2. Brad and I

On that same trip to Italy and France, we met up with my little brother in Chi Phi, Brad, who was skiing with his family in Cervinia. I felt a unique kinship with him, so it was especially nice to meet outside of college. Here we are at a church. Taking photos with landmarks and people, it’s a way of saying, ‘I was here and this is someone that I care about.’

3. Before the Renovation

Late 90s with my cousin Lianne at The Met in NYC. The Egyptian Wing was my favorite; the glass enclosures densely filled with thousands of arranged artifacts. It felt as if everything was accounted for, from tiny stone scarabs to large statues carved from wood. I still get a sense of pleasure from the organization of objects. The galleries have been reinstalled, so they no longer look like this image.

4. Tainan Jade Market

Memories are not reliable, but bits and pieces can come together to form a story. I called my mom to ask when Grandpa Chen passed away. She didn’t remember so we had to figure out when Grandma Chen passed to backtrack from that date. That didn’t work either, so I texted my sister because she was closer to him. While waiting for her response, little details began to emerge. I was taking Japanese as a sophomore (1998) and I wrote a letter to him. When we met again that summer in Taiwan, he taught me the honorific form of “I;” Watakushi. We went to jade and antique markets together because we both shared an appreciation for beautiful, old, and worn things.

5. Before and After

Around 2003, I lived in a restored townhouse in the historic Paulus Hook neighborhood of Jersey City. There was a potted sago palm at a shop in Manhattan that I admired, so it came home with me on the PATH Train. Sadly, I was never any good at taking care of plants and it died soon after. At first, the tips of its fronds turned yellow. I tried to give it more water, but the green, upright palm turned into a wilted, brown mass within months. I still have the cobalt glazed terra cotta pot that it came in. It’s currently a catch-all for laundry and mail in our bathroom.

6. Water Fountains

This photo is time stamped 6 13 ‘03. It was taken in Spain, most likely in Madrid. I went there at least once a year between 1997 to 2004 for the tapas, AVE trains, Reina Sofia and the Thyssen, the language, Loewe, and the Palace Hotel. Shuffling through my old photographs, I found trivial images of water fountains among other landmarks without personal significance that I could recall. Such generic shots do not mean anything to me now, but they were likely significant, world creating markers as a young adult who was eager to embody and portray success.

7. Curio Cabinet

My dad had an eye for worn furniture found at garage sales and along sidewalks. I liked this tall curio cabinet except for its color and decorative mesh panels that originally obscured the shelves. At first, I wanted to paint it white to match my bedroom, but then I decided to paint one of my walls yellow to match it instead. Time stamped ’01, I was living at home with my parents in Floral Park, NY after college, and I was commuting 1.5 hours to work at the Grand Hyatt New York in midtown Manhattan. Here’s my collection of antique fair finds, dried flowers, books, and little objects. I collected blue and white ceramics, especially flow blue china. My interior design references were magazines from the library like House Beautiful, Metropolitan Home, House & Garden, and Better Homes. I shopped for bedding and other accessories at places like Pottery Barn, William’s Sonoma, Ralph Lauren, ABC Carpet & Home, the Bombay Company, and the Met’s gift shop to cultivate an eclectic, old-world aesthetic.

8. Sharp Turn

9/11 pierced the delirious illusion of my ‘mainstream success’ persona. I felt somewhat tired of my dedication toward work at a relatively low paid yet glamorized profession in hospitality. I also had to come to terms with my sexuality because it was no longer sustainable to deny it. There was gay.com and gaydar.co.uk to chat online and meet in person with others like me. At first, there was David and then there was Andy. Up to this point in life, my dreams were all attainable so I could not comprehend my failures in romance. Thank God I had the right sense of mind to fix myself first over my career. At the time, I thought that I was losing my mind to abandon my promotion to the Hyatt Regency in Reston, Virginia to return to NYC. This image was taken at the wheel of my car, turning away from an idyllically suburban apartment complex in Reston.

9. Not Yet a Memory

Before that decision was made to leave Reston, I took a train ride back home to reunite with friends and family for a weekend. It was clear that I wasn’t ready for the lights, the noise, the hustle, the crowded streets, and the subway to be distant memories.

10, 11, 12. Nine Images, Three Images, Forty-two Images

In the 90s, amateur photos were taken with hand-held, point and shoot cameras. Such descriptors are redundant now, but they were important when cameras were not ubiquitous. I had a 35mm film Canon with a wireless remote and I always kept it close, mostly to document my development. Photos were proof of a strategically cultivated persona. They helped me to see myself among the people in my life, and it was a means to control my story. There are similarities as well as stark differences between the physical photo albums of yesterday and the digital feeds of today’s social media platforms. For Nine images, Three Images, and Forty-two Images, I attempted to organize tie boxes full of my old photos. Categories such as me, me with people, people (not me), places, hotels, work, family, and Highschool + Before were defined, but it took multiple attempts to land on this naming convention. Photographs from these piles were selected and stacked like desktop icons and recorded as an ink rubbing before they were reshuffled into the mix.

Side Note: Now Images

Analog Photography moved at a manageable pace. The time that it took to finish a roll of film and develop at the local convenience store inevitably meant that images were of the past. Past images were memories of places that were visited, people that we spent time with, and events that occurred. Images of memories offered opportunities to look back and reflect. Now, with our digitally enhanced capacity to store memories, one would expect a refined ability to track personal and collective growth. The opposite is true. Instagram does not welcome memories let alone reflections. This is a significant difference between the delayed, film processed, photo archives of yesterday and the instant, digital, running feeds of today. In this digital era, Now Images are taken to establish the now across social media platforms while the intention to save a memory becomes a foreign concept. The past no longer holds relevance ever since the monetization of “presence” was established by platforms such as Instagram. The stories feature reinforces this always-in-the-moment fiction. Amateur photographers aka content creators are led to believe that they are living the moment when they post a story. At the same time, they are removing themselves from participating in the moment to post a Now Image so that others can like and comment now to reinforce a Now Loop. This “best self” projection is based on an unattainable future self because the subject matter always remains trapped within the now. Look at me now, look at what I’m doing now, look at where I am now, see how I am now, see where I’m going now. Photographs can no longer afford to be still images. They must run tirelessly toward the next Now Image before it expires within 24 hours.

13. Rack: 144 Washington

I lived at the Chi Phi House as a senior at Binghamton University. My unit was at the top of this staircase, immediately above the Party Room. I escaped most fraternity duties at this time because of my front desk clerk job at The Historical Hotel de Ville. I was so ready to graduate, to enter the real world, to wear a suit, to grow up. I look back now as the acceleration of life feels unabating, thinking, why was I in such a rush? Although the fraternity greatly shaped who I am today, I outgrew the lifestyle quickly. The decorated paddles along the staircase signified the pledge classes that came before mine. Highly compressed interior moments of a young man navigating masculinity are expanded across this wobbly rack. Coiled wire was hand bent to hold a succession of ink rubbings pulled from a single image.

14. Rack: All

Images hold emotional weight, perhaps even more so as a physical photograph. In this installation, my old photos are cut, folded, warped, punctured, and braced into structural supports to elevate grids of handwoven metal wire racks a few inches off the floor. Ink rubbings lay flat across these racks, held down by weights made of clay encased in plastic. They appear as if they are being air dried and preserved for future consumption.

15. Rack: Framework

Original photographs taken during my teens to early twenties are embedded within folds of wet, clay slabs encased in plastic. These frames fail to protect their contents. Instead, they warp and reshape images held within as the clay air dries and shrinks. They rest on top of handwoven metal wire racks that allude to the curing process of storable sustenance. Framework demonstrates the emotional transformation that memories endure over time. Memories can be felt within our organs, muscles, and bones. They are stored within our bodies and provide necessary nourishment throughout our lifelong development.

Studio Visit by Chad Benjamin Potter

Things look different up-close, in real life. Winter Break as an undergrad, late 90s, my cousin Ellen and I took a trip to Italy and France. One of my highlights was coming across Alberti’s façade for the Basilica Santa Maria Novella in Florence. I learned about the building in an intro to architecture course at Binghamton University. We walked alongside it until the street opened onto a square. I turned around and there it was with a fountain, a bunch of pigeons, and a sunset. Alberti’s façade was a black and white image until I saw it in person.

2. Brad and I

On that same trip to Italy and France, we met up with my little brother in Chi Phi, Brad, who was skiing with his family in Cervinia. I felt a unique kinship with him, so it was especially nice to meet outside of college. Here we are at a church. Taking photos with landmarks and people, it’s a way of saying, ‘I was here and this is someone that I care about.’

3. Before the Renovation

Late 90s with my cousin Lianne at The Met in NYC. The Egyptian Wing was my favorite; the glass enclosures densely filled with thousands of arranged artifacts. It felt as if everything was accounted for, from tiny stone scarabs to large statues carved from wood. I still get a sense of pleasure from the organization of objects. The galleries have been reinstalled, so they no longer look like this image.

4. Tainan Jade Market

Memories are not reliable, but bits and pieces can come together to form a story. I called my mom to ask when Grandpa Chen passed away. She didn’t remember so we had to figure out when Grandma Chen passed to backtrack from that date. That didn’t work either, so I texted my sister because she was closer to him. While waiting for her response, little details began to emerge. I was taking Japanese as a sophomore (1998) and I wrote a letter to him. When we met again that summer in Taiwan, he taught me the honorific form of “I;” Watakushi. We went to jade and antique markets together because we both shared an appreciation for beautiful, old, and worn things.

5. Before and After

Around 2003, I lived in a restored townhouse in the historic Paulus Hook neighborhood of Jersey City. There was a potted sago palm at a shop in Manhattan that I admired, so it came home with me on the PATH Train. Sadly, I was never any good at taking care of plants and it died soon after. At first, the tips of its fronds turned yellow. I tried to give it more water, but the green, upright palm turned into a wilted, brown mass within months. I still have the cobalt glazed terra cotta pot that it came in. It’s currently a catch-all for laundry and mail in our bathroom.

6. Water Fountains

This photo is time stamped 6 13 ‘03. It was taken in Spain, most likely in Madrid. I went there at least once a year between 1997 to 2004 for the tapas, AVE trains, Reina Sofia and the Thyssen, the language, Loewe, and the Palace Hotel. Shuffling through my old photographs, I found trivial images of water fountains among other landmarks without personal significance that I could recall. Such generic shots do not mean anything to me now, but they were likely significant, world creating markers as a young adult who was eager to embody and portray success.

7. Curio Cabinet

My dad had an eye for worn furniture found at garage sales and along sidewalks. I liked this tall curio cabinet except for its color and decorative mesh panels that originally obscured the shelves. At first, I wanted to paint it white to match my bedroom, but then I decided to paint one of my walls yellow to match it instead. Time stamped ’01, I was living at home with my parents in Floral Park, NY after college, and I was commuting 1.5 hours to work at the Grand Hyatt New York in midtown Manhattan. Here’s my collection of antique fair finds, dried flowers, books, and little objects. I collected blue and white ceramics, especially flow blue china. My interior design references were magazines from the library like House Beautiful, Metropolitan Home, House & Garden, and Better Homes. I shopped for bedding and other accessories at places like Pottery Barn, William’s Sonoma, Ralph Lauren, ABC Carpet & Home, the Bombay Company, and the Met’s gift shop to cultivate an eclectic, old-world aesthetic.

8. Sharp Turn

9/11 pierced the delirious illusion of my ‘mainstream success’ persona. I felt somewhat tired of my dedication toward work at a relatively low paid yet glamorized profession in hospitality. I also had to come to terms with my sexuality because it was no longer sustainable to deny it. There was gay.com and gaydar.co.uk to chat online and meet in person with others like me. At first, there was David and then there was Andy. Up to this point in life, my dreams were all attainable so I could not comprehend my failures in romance. Thank God I had the right sense of mind to fix myself first over my career. At the time, I thought that I was losing my mind to abandon my promotion to the Hyatt Regency in Reston, Virginia to return to NYC. This image was taken at the wheel of my car, turning away from an idyllically suburban apartment complex in Reston.

9. Not Yet a Memory

Before that decision was made to leave Reston, I took a train ride back home to reunite with friends and family for a weekend. It was clear that I wasn’t ready for the lights, the noise, the hustle, the crowded streets, and the subway to be distant memories.

10, 11, 12. Nine Images, Three Images, Forty-two Images

In the 90s, amateur photos were taken with hand-held, point and shoot cameras. Such descriptors are redundant now, but they were important when cameras were not ubiquitous. I had a 35mm film Canon with a wireless remote and I always kept it close, mostly to document my development. Photos were proof of a strategically cultivated persona. They helped me to see myself among the people in my life, and it was a means to control my story. There are similarities as well as stark differences between the physical photo albums of yesterday and the digital feeds of today’s social media platforms. For Nine images, Three Images, and Forty-two Images, I attempted to organize tie boxes full of my old photos. Categories such as me, me with people, people (not me), places, hotels, work, family, and Highschool + Before were defined, but it took multiple attempts to land on this naming convention. Photographs from these piles were selected and stacked like desktop icons and recorded as an ink rubbing before they were reshuffled into the mix.

Side Note: Now Images

Analog Photography moved at a manageable pace. The time that it took to finish a roll of film and develop at the local convenience store inevitably meant that images were of the past. Past images were memories of places that were visited, people that we spent time with, and events that occurred. Images of memories offered opportunities to look back and reflect. Now, with our digitally enhanced capacity to store memories, one would expect a refined ability to track personal and collective growth. The opposite is true. Instagram does not welcome memories let alone reflections. This is a significant difference between the delayed, film processed, photo archives of yesterday and the instant, digital, running feeds of today. In this digital era, Now Images are taken to establish the now across social media platforms while the intention to save a memory becomes a foreign concept. The past no longer holds relevance ever since the monetization of “presence” was established by platforms such as Instagram. The stories feature reinforces this always-in-the-moment fiction. Amateur photographers aka content creators are led to believe that they are living the moment when they post a story. At the same time, they are removing themselves from participating in the moment to post a Now Image so that others can like and comment now to reinforce a Now Loop. This “best self” projection is based on an unattainable future self because the subject matter always remains trapped within the now. Look at me now, look at what I’m doing now, look at where I am now, see how I am now, see where I’m going now. Photographs can no longer afford to be still images. They must run tirelessly toward the next Now Image before it expires within 24 hours.

13. Rack: 144 Washington

I lived at the Chi Phi House as a senior at Binghamton University. My unit was at the top of this staircase, immediately above the Party Room. I escaped most fraternity duties at this time because of my front desk clerk job at The Historical Hotel de Ville. I was so ready to graduate, to enter the real world, to wear a suit, to grow up. I look back now as the acceleration of life feels unabating, thinking, why was I in such a rush? Although the fraternity greatly shaped who I am today, I outgrew the lifestyle quickly. The decorated paddles along the staircase signified the pledge classes that came before mine. Highly compressed interior moments of a young man navigating masculinity are expanded across this wobbly rack. Coiled wire was hand bent to hold a succession of ink rubbings pulled from a single image.

14. Rack: All

Images hold emotional weight, perhaps even more so as a physical photograph. In this installation, my old photos are cut, folded, warped, punctured, and braced into structural supports to elevate grids of handwoven metal wire racks a few inches off the floor. Ink rubbings lay flat across these racks, held down by weights made of clay encased in plastic. They appear as if they are being air dried and preserved for future consumption.

15. Rack: Framework

Original photographs taken during my teens to early twenties are embedded within folds of wet, clay slabs encased in plastic. These frames fail to protect their contents. Instead, they warp and reshape images held within as the clay air dries and shrinks. They rest on top of handwoven metal wire racks that allude to the curing process of storable sustenance. Framework demonstrates the emotional transformation that memories endure over time. Memories can be felt within our organs, muscles, and bones. They are stored within our bodies and provide necessary nourishment throughout our lifelong development.

Studio Visit by Chad Benjamin Potter

國語

It’s a habit of mine to take a lot of images when I visit exhibitions to document the art on display. In part, I’m enacting the care that I hope others will take while viewing my own work. I’m also taking visual notes to help me remember what and how I’ve seen. I rarely feel as if I’ve had enough time to spend with the art, the space, and the wall text, so its an exercise in recollection. This habit extends outside of the art gallery whenever I see a potential reference for my studio practice. Here’s a mix of photos taken with an iPhone over the years, and a few links that relate to the broader subject of display.

I’d like to thank Nicole Seisler for the invitation and Alexis Brunkow, Holly Coley, E.C. Comstock, Rebecca Elves, Ana Henton, Andy Li, Emma Logan, Al Oliva, Alex Simpson, and Kate Strachan for four weeks of conversing/working together at A-B Projects. (this project page is continuously under construction)

Risers within Encasements on Pedestals on a Platform

1-8: Ron Nagle, Handsome Drifter, BAMPFA

Point of View

1-3: Vincent Fecteau, Wattis Institute

Museology

1. Victoria & Albert Museum

2. Metropolitan Museum of Art

3. Brooklyn Museum

4. Museum of Natural History

5. MoMA

6. The Israel Museum

Invisible Armatures

1. BAMPFA

2. Asian Art Museum

3-4. Legion of Honor

Protective Measures

1. Kristen Morgin, Hammer Museum

2. Isamu Noguchi, The Noguchi Museum

3. Kondo Takahiro, Asian Art Museum

4. Erica Mahinay, Hammer Museum

Monument to Nameless Sacred Remains Sleeping in the Boat of Memory, 1998-2002, Mu Tsan, Mixed media, Collection of KMFA

On the Floor

Liz Larner, SculptureCenter

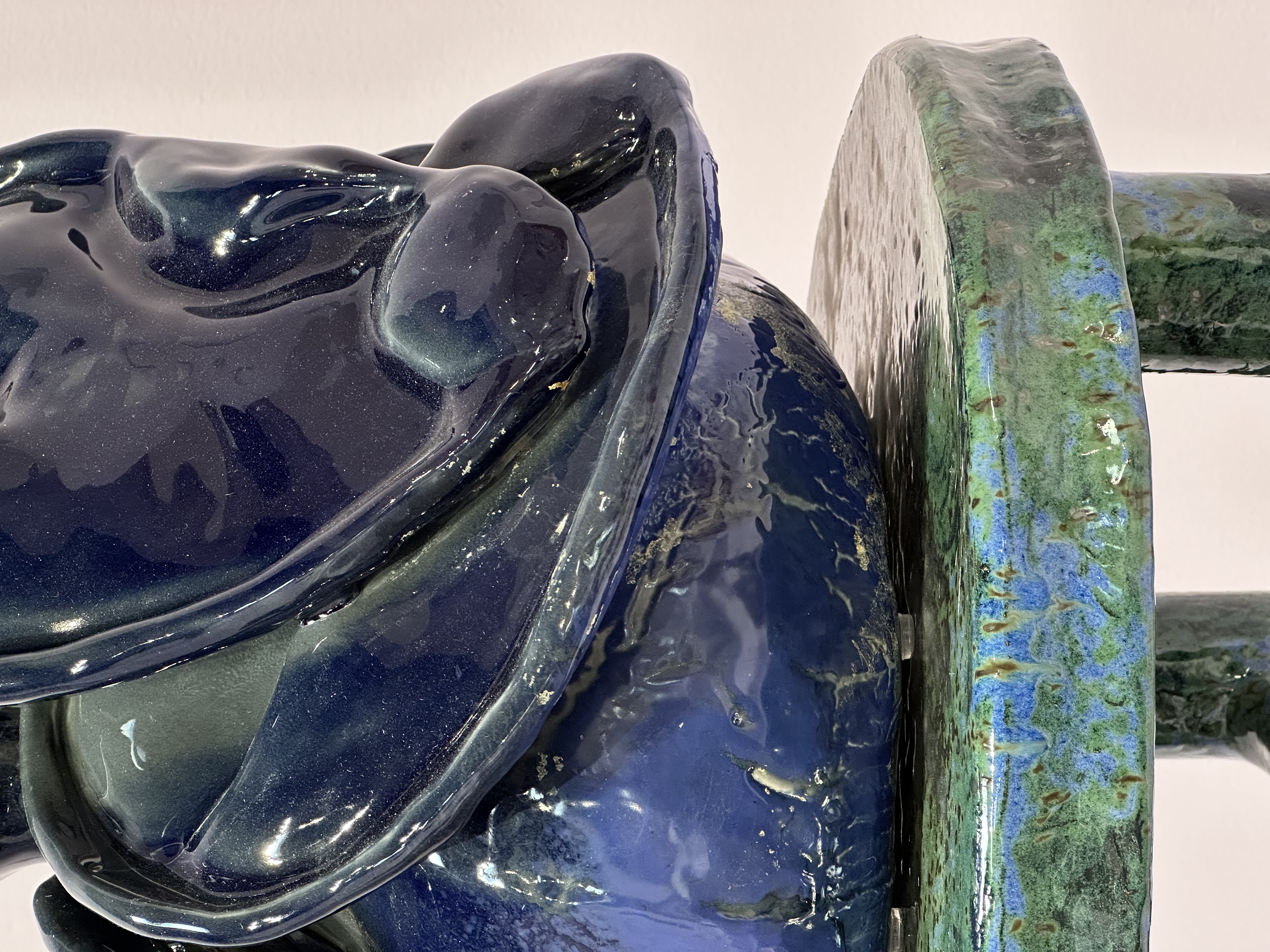

Gabriel Chaile, New Museum

Anna Sew Hoy, SFMoMa

Sahar Khoury, Rebecca Camacho Presents

Michael Dean, South London Gallery

Raven Halfmoon, Steve Turner

Dolores Furtado, MoMA PS1

On the Wall

Liz Larner, SculptureCenter

Erin Jane Nelson, New Museum

Jim Melchert, Gallery 16

Manal Kara

Pedestal Permutations

Gala Porras Kim, Fowler Museum

Clay Pop, Jeffrey Deitch

Evgeny Antuflev

Rose B Simpson, BAMPFA

Sarah Lucas, New Museum

Nicki Green, BAMPFA

Ruby Neri, BAMPFA

Taipei National University of the Arts

Victoria & Albert Museum

The Whitney Museum

Maryam Yousif, The Pit

Ken Price, Matthew Marks

Rose P. Simpson

Low Riser

Ana Mendieta

Sterling Ruby

Isamu Noguchi

Wangechi Mutu

Arthur Simms, Karma

Kang Seung Lee, Hammer Museum

Architecture Exhibition, Centro Centro

Richard Deacon, Tate Britain

El Anatsui, Cantor Arts Center

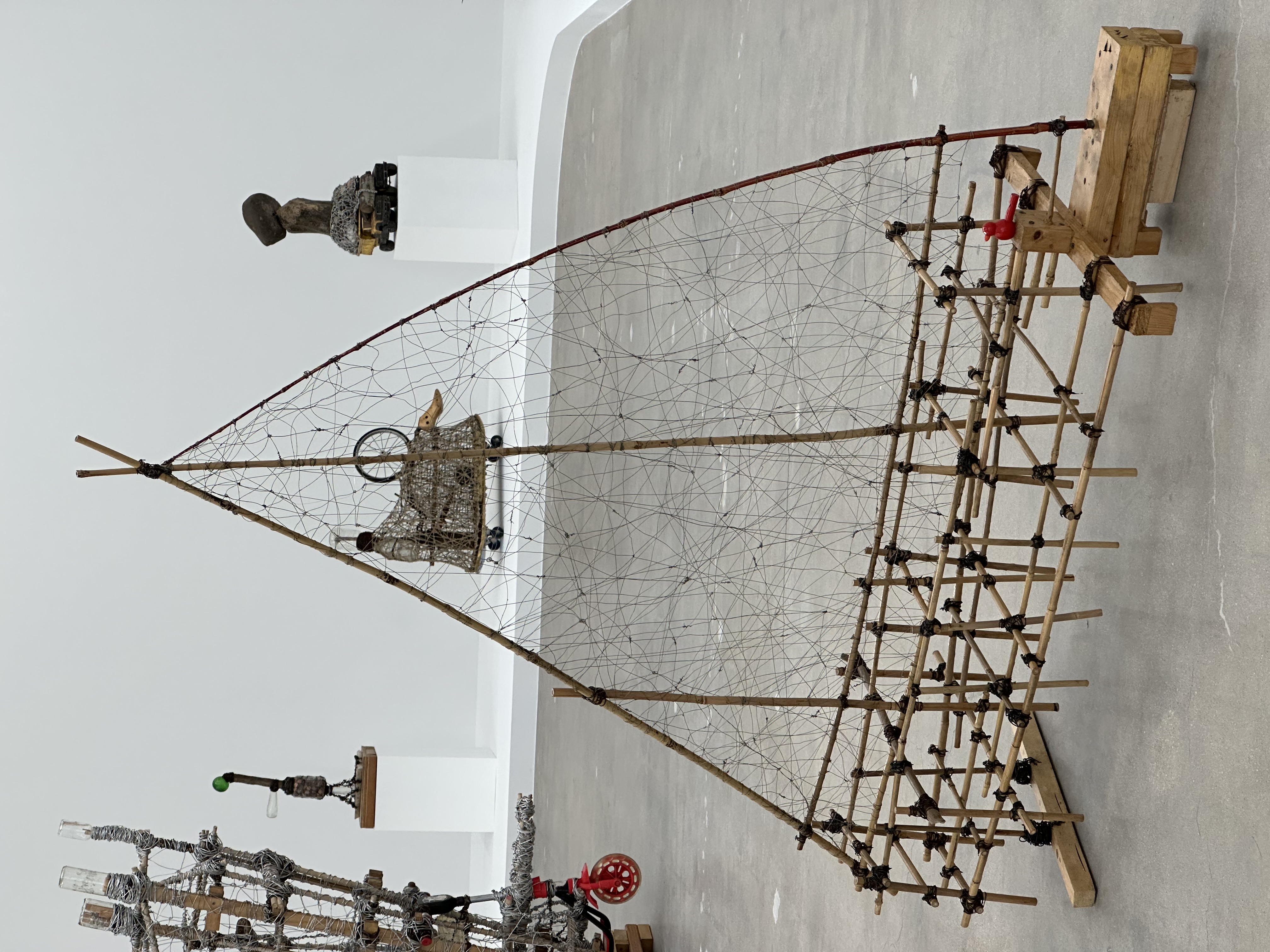

Jumana Manna, Break, Take, Erase, Tally

Nicole Eisenman, Procession, 2019, mixed media installation, Whitney Museum

Meret Oppenheim, MoMa

Something Else

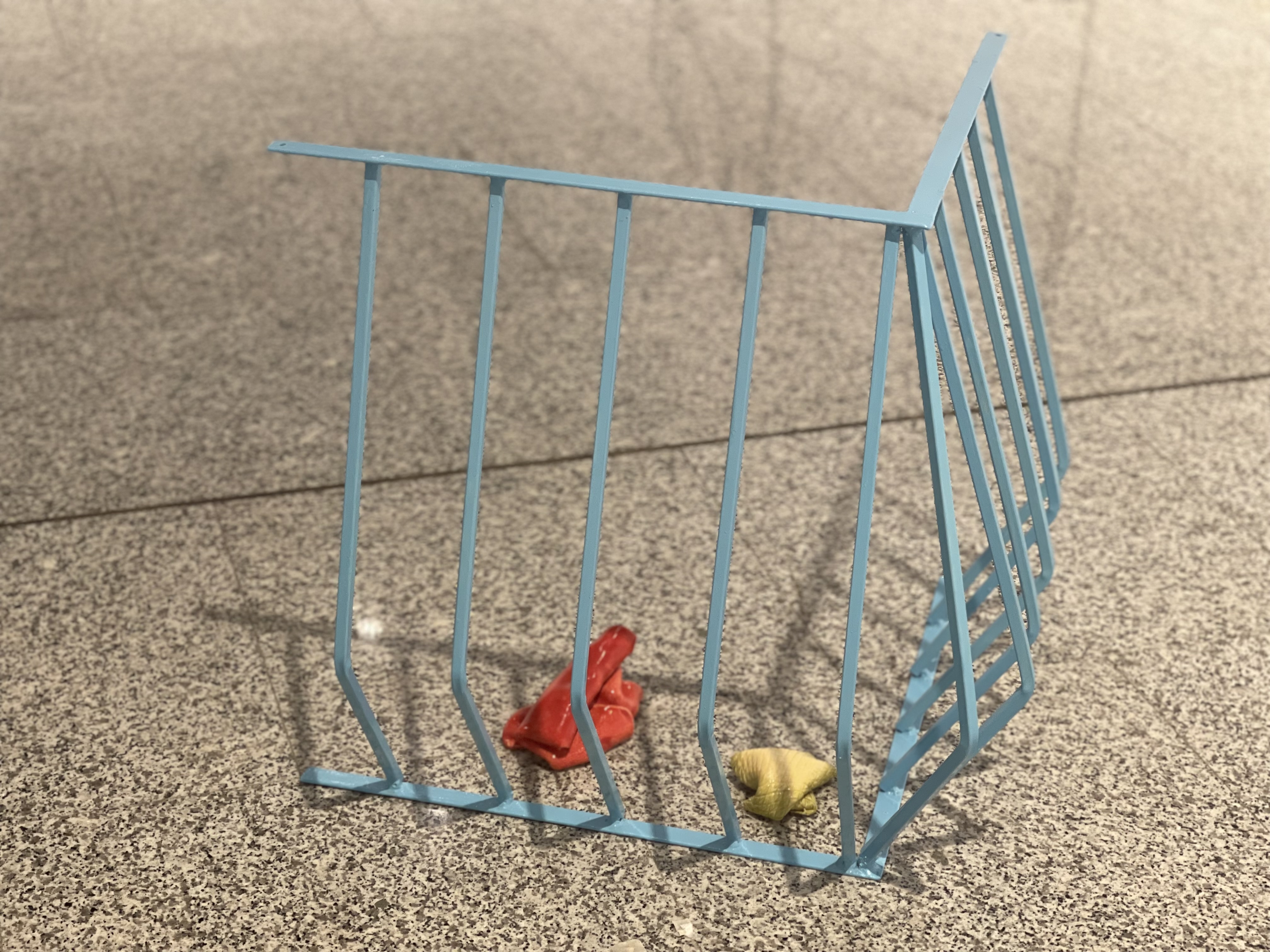

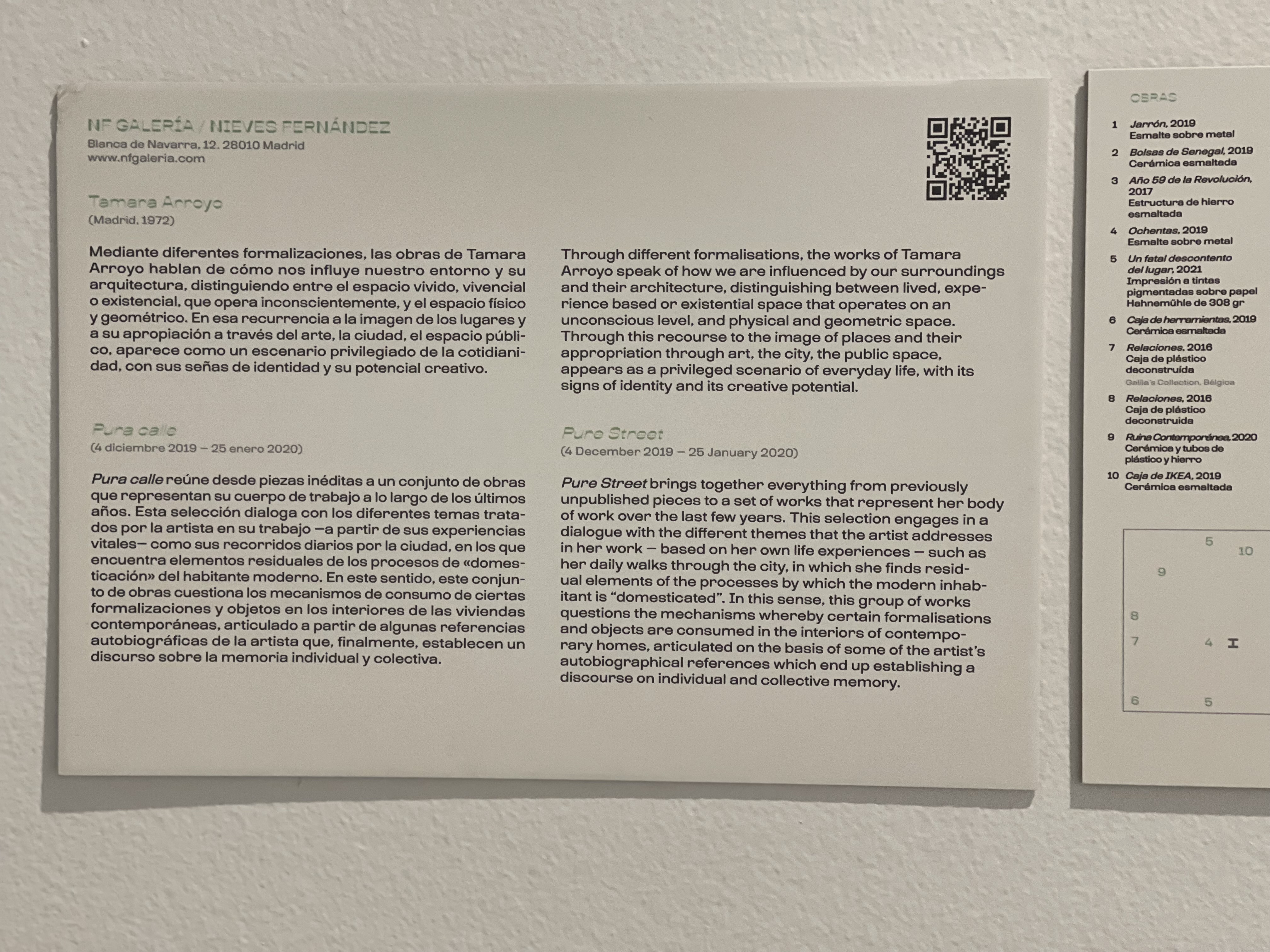

Tamara Arroyo, Pura calle, Centro Centro

Surfaces

Perishables

The Display as a Medium

Stephanie Syjuco, The Berlin Wall

Kamrooz Aman, Ancient Through Modern...

Gala Porras-Kim: Containment & Framing

The Expansive Pedestal

Tania Bruguera, Tatlin’s Whisper #5

Tania Bruguera, Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana version)